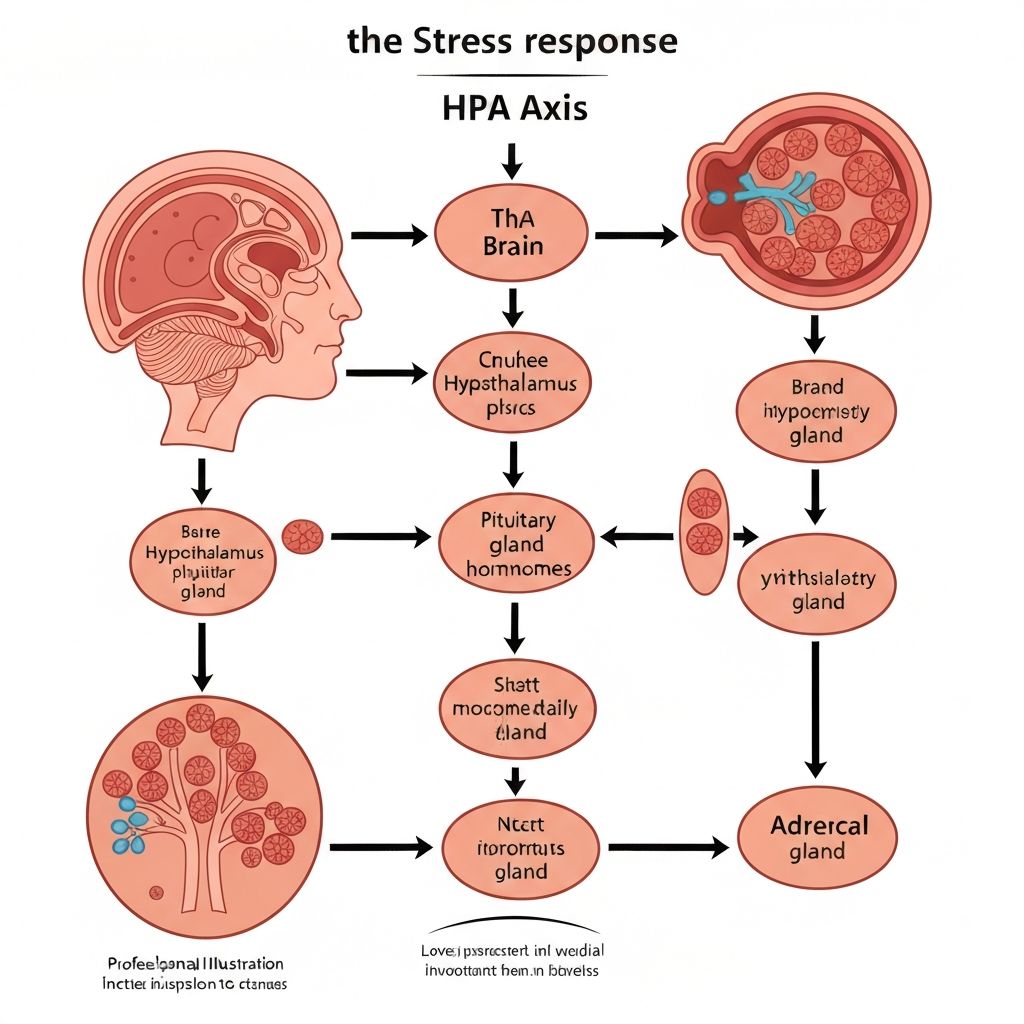

Physiological and Behavioural Links Between Chronic Stress and Body Mass

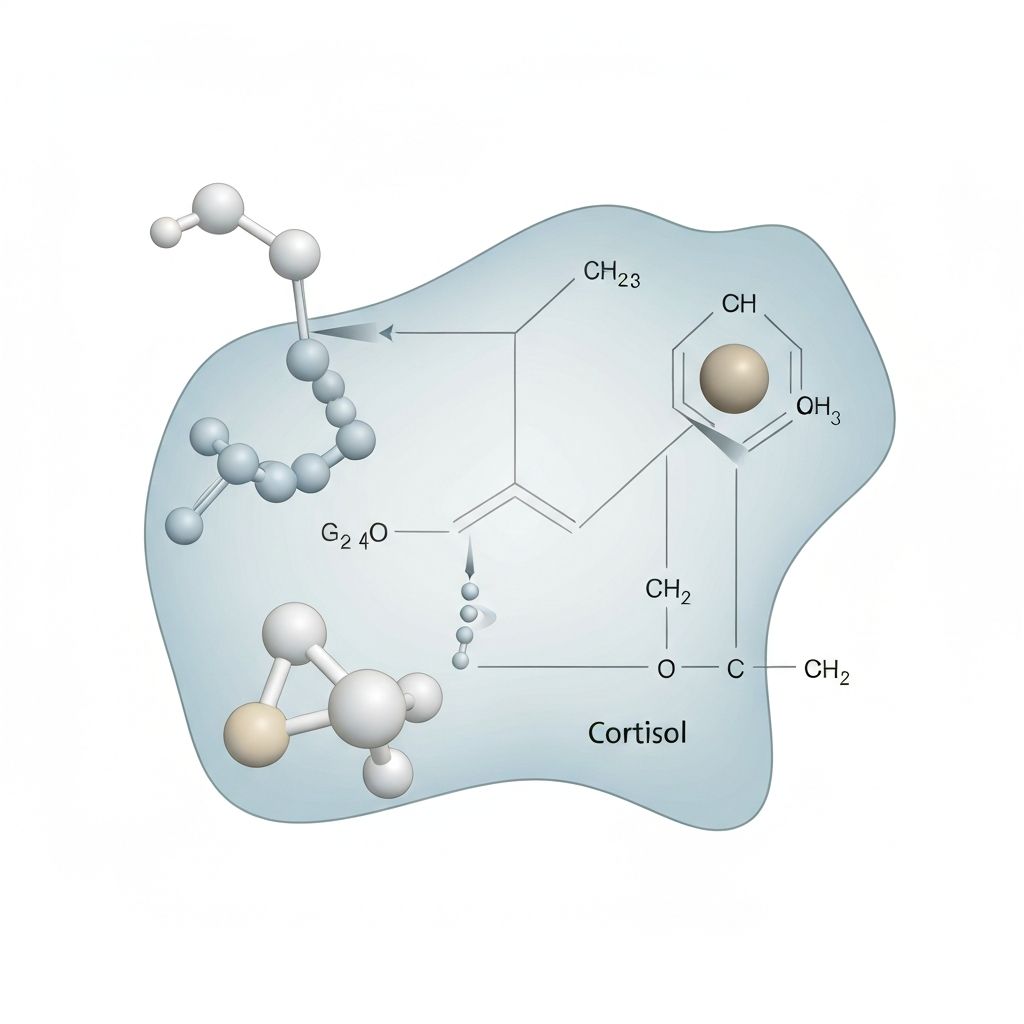

An educational resource exploring the mechanisms of stress physiology, hormonal responses, and observed associations with body composition.

Educational content only. No promises of outcomes.